Oil futures trading speculation

Protecting coastal mangrove forests from development can cost-effectively achieve CO2 emissions reductions on par with taking millions of cars off the roads, according to a recent study by experts at RFF and the University of California, Davis. RFF has unveiled two tools to help policymakers, experts, and the public better understand the complex process of shale gas development as it unfolds across the country.

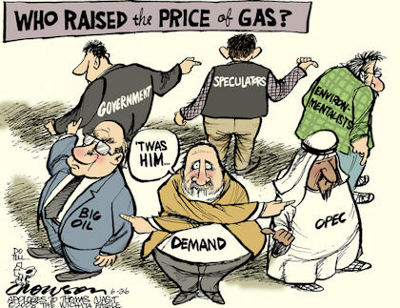

The populist view is that financial trading is responsible for the oil price spike of — But as James L. Smith explains, ongoing research points elsewhere. Will historic air pollution regulations have dramatic effects on electricity prices and the generation mix? No, but cheap natural gas and falling demand might. This infographic shows how carbon tax revenue from the electricity sector is uncertain and dependent on the level of the tax and conditions such as natural gas prices.

The price of crude oil seems erratic. It swings up, then down, in endless and seemingly inexplicable cycles. The economic significance of these price swings is underscored by the fact that crude oil comprises the single largest component of global trade, far outranking the combined value of clothing, food, and automobiles.

Economists have identified a number of factors, including the relative rigidity of supply and demand for oil, as well as the magnitude and frequency of unexpected shocks that periodically disrupt the market.

Any disruption, whether to demand or supply, requires extraordinarily large price adjustments to persuade producers and consumers to adjust their behavior as required to restore equilibrium to the market. As a rule of thumb, a 1 percent disruption to the supply of oil creates a corresponding 10 percent jump in the price. Libya provides a real-word example: Libyan output comprises roughly 2 percent of total world production of crude oil, and global prices jumped roughly 20 percent when Libyan shipments were blocked by revolution last year.

Alongside these fundamental reasons for the volatility of oil prices, there are persistent concerns that excessive speculation and financial trading in the futures market have played a role. For example, the total number of crude oil futures contracts held by hedge funds quintupled between and Although the number of contracts held by commercial traders—producers and consumers of oil who use futures contracts to hedge their natural exposure to price risk—also grew, the increase was less and their market share declined from 67 percent to 50 percent between those years.

Since the financial influx was accompanied by a steep ascent in oil prices, it is natural to ask whether this represents coincidence or causality.

The populist view is quite simple: Applications of this principle to certain individual commodities may be appropriate. For example, recent recordbreaking prices of the best vintages of fine Bordeaux wine can safely be attributed to the new and large influx of Chinese demand chasing what is an absolutely fixed supply of the product. But attempts to extend the logic of the quantity theory to the operation of futures markets fail badly.

The first failing arises because the quantity of futures contracts, unlike the supply of Bordeaux, is not fixed, but expands or contracts to equilibrate the market. And if he wants another, it can be created and sold as well.

CL1! — free chart and prices Light Crude Oil Futures:NYMEX | TradingView

If only that were true of fine Bordeaux. The second failing is to assume that an influx of money necessarily creates buying pressure.

In fact, each contract initially purchased by an investor will be resold by that same investor before the contract expires. Every futures contract purchased by an investor is subsequently sold back by that same investor, and this fact is known and anticipated by all investors in the market. Thus, for each and every contract, buying pressure equals selling pressure—which ultimately equals no pressure.

Futures trades neither add nor remove oil from the physical supply chain, where the spot price of oil is determined. Thus, an influx of money into the futures market does not, per se, move the price of oil. Only a change in expectations regarding market conditions can do that. This leads us to consider the alternative hypothesis of contagion, a channel by which financial traders may conceivably impact the price. If heightened trading by financial investors alters the expectations of commercial traders, then any resulting adjustments to production, inventories, or consumption could move prices to a new level.

Was this behind the recent price spikes? Economists tend to believe that prices reflect expectations, and when expectations change, prices follow. It is an empirical question whether the actions of financial traders had such an impact on expectations and prices during the oil price spike.

Does Speculation Drive Oil Prices? | Resources for the Future

Fortunately, empirical research has begun to provide some answers. Most relevant to the question of placing new restrictions on futures trading are studies that focus directly on the impact of trades made by hedge funds and other financial investors. Using comprehensive data from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission CFTC that reflect individual trading patterns in the NYMEX WTI crude oil futures contract, these studies investigate whether price movements typically have been preceded by changes in the trading positions of hedge funds and other types of financial investors.

If the accumulation of contracts by hedge funds indeed causes prices to rise, then such a pattern should be apparent in the historical data. But researchers have found that in fact, the opposite pattern emerges. From to , hedge funds and other financial traders seem to have adjusted positions in response to price movements; their trades do not appear to have caused price movements.

The behavior of other commodities not widely traded on futures markets provides corroborating evidence and suggests that the oil price spike was probably due to the unprecedented increase in demand for all industrial commodities that emanated from India and China, rather than the financialization of the futures market.

Studies by the International Energy Agency and other researchers show that prices of non-traded commodities like manganese, rice, cobalt, and coal all tended to rise and fall in unison with oil between and , without any prompting or prodding by futures traders.

Other strands of current research bear on the question at hand, albeit from somewhat different perspectives. For example, simple attempts to model and measure fluctuations in the basic fundamental determinants of oil prices leave about 25 percent of total price movements unexplained.

One interpretation is that the residual percentage might be due to speculation. Another is that the unexplained portion of observed price movements is due as in many econometric models to model misspecification, left-out variables, and unaccounted shocks that have nothing to do with speculative trading. The question has been subjected to more rigorous analysis in the form of structural vector autoregressive SVAR models. Roughly speaking, this approach attempts to isolate and distinguish the several causes of observed price movements and measure their relative importance.

It is based on the hypothesis that different types of shocks leave distinctive fingerprints on the price of oil. For example, demand shocks associated with unexpected changes in the global business cycle should cause global oil production, global economic activity, and the price of oil all to increase, whereas supply shocks should cause the price of oil to increase while global oil production and economic activity both fall. Shocks to the speculative demand for oil should cause inventories to accumulate at the same time that oil prices rise.

By searching through all these related time series for the characteristic fingerprints, the SVAR technique apportions observed variation in oil prices to its various components. The most straightforward application of the SVAR technique finds historical evidence that speculation moved oil prices on numerous occasions—in , , , and late —which accords with other anecdotal evidence.

It provides little support, though, for the notion that the oil price surge between and was due to speculation. Rather, the analysis identifies a series of negative supply shocks and, more significantly, a series of positive demand shocks as causes of the price spike.

Empirical research on the impact of financial trading is subject to many limitations, and while research remains ongoing, it seems prudent to keep an open mind.

Yet any summary of the peer-reviewed research produced so far would place the weight of evidence on the side that market fundamentals, not financial speculation, drive the price of oil. Despite ongoing research, the question of whether oil speculation caused the recent spike in oil prices appears settled to some observers.

New regulatory policies are taking shape in the United States and elsewhere based on the assumption that financial speculation and excessive futures trading push oil prices away from fundamental values. As part of the Dodd-Frank financial overhaul, for example, the Federal Reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission, and CFTC are circulating reforms that will impose new costs on financial investors and limit their investment in futures contracts.

Whether these policies will have the intended effect remains to be seen— the channel by which financial trading might impact commodity prices is anything but transparent. Buyuksahin, Bahattin, and Jeffry H. Do Speculators Drive Crude Oil Futures Prices? The Energy Journal 32 2: Fattouh, Bassam, Lutz Kilian, and Lavan Mahadeva.

The Role of Speculation in Oil Markets: What Have We Learned so Far? Testing the Masters Hypothesis in Commodity Futures Markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives 23 3: Commodity Index Investing and Commodity Futures Prices. Journal of Applied Finance 20 1: Resources for the Future conducts rigorous economic research and objective analysis to help leaders craft smarter policies about natural resources, energy, and the environment.

Resources for the Future P Street NW, Suite Washington, DC Phone: Published since , Resources ISSN contains news of research and policy analysis on environmental, energy, and natural resource issues. The views offered are those of the contributors and should not be attributed to Resources for the Future, its directors, or its officers. Articles may be derived from related RFF publications.

How does oil speculation raise gas prices? | HowStuffWorks

No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means without permission from the publisher. Contact Adrienne Young at young rff.

Share Close Share Drawer Facebook LinkedIn Twitter Email.

Table of Contents Close Table of Contents Contents Resources Magazine: Challenges at the Intersection of Scarcity, Growth, and Risk Goings On Commentary: Managing Water through Innovative Collaboration: An Interview with Lynn Scarlett Blue Carbon: A Potentially Winning Climate Strategy Protecting coastal mangrove forests from development can cost-effectively achieve CO2 emissions reductions on par with taking millions of cars off the roads, according to a recent study by experts at RFF and the University of California, Davis.

Managing the Risks of Shale Gas: The Latest Results from RFF's Initiative RFF has unveiled two tools to help policymakers, experts, and the public better understand the complex process of shale gas development as it unfolds across the country.

Will Natural Gas Vehicles Be in Our Future? Does Speculation Drive Oil Prices? Clean Air Regulations and the Electricity Sector Will historic air pollution regulations have dramatic effects on electricity prices and the generation mix? Answering Questions about a Carbon Tax This infographic shows how carbon tax revenue from the electricity sector is uncertain and dependent on the level of the tax and conditions such as natural gas prices.

Inside RFF Close Table of Contents. Resources Article Does Speculation Drive Oil Prices? Nov 26, James Smith. Facebook LinkedIn Twitter Email. DOWNLOAD Resources Article Does Speculation Drive Oil Prices? Energy and Electricity Subtopics: Oil Related Content Resources Magazine Resources Magazine: Subscribe to Resources Magazine Sign up to receive each new issue of Resources via email.

RFF Email Options RFF Connection monthly Event invitations and notices Resources magazine three times per year RFF on the Issues weekly RFF's blog, Common Resources Press releases and media notes Opportunities to support RFF. Resources for the Future Resources for the Future conducts rigorous economic research and objective analysis to help leaders craft smarter policies about natural resources, energy, and the environment. Research People Events Blog About Search our Site Search.

Contact Resources for the Future P Street NW, Suite Washington, DC Phone: